From the school we set off with a group of children whom we are visiting today. As we walk, they cheerfully chatter away. During the afternoon and evening, children from one family always accompany us to the next one. We walk past the fields of corn and peas. Here the children pick some, as we walk past a chorten and a prayer wheel, which must be span.

As we approach the dwellings, a little girl shows us – this is where I live! A large animal stands in front of the house. It’s bigger than a cow and with bushy fur. It’s a dzo, an intergrade to yak, which live in the highest altitudes, since with its thick fur it would be too hot down here in the valley. I photograph the house but it turns out that I am wrong – this isn’t the house of the girl. The family we are visiting lives next door, in what I first assumed to be a ruin…

There are a few steps down a wooden ladder, a flat roof, an entrance to the kitchen; we can’t see anything else. There is probably be a prayer room somewhere and that’s it. The family doesn’t own any animals and is very poor.

When we visit the families, we are led either into the kitchen or into the guest room. We sit down at a low coffee table and immediately get a sweet spicy tea and biscuits. We talk about school and everyday life of the family. Other family visits follow a similar pattern – tea, biscuits, chat and a group photo.

Although the houses look very similar from the outside, we always find something interesting inside. We learn new information about the life here or hear a story with a touch of a storybook mystery. Although it may seem strange to us that these stories are said in a serious way, it’s done out respect for traditional customs and the laws of nature. People here live in close connection to nature and adapt to the climate, which has a very short growing season here, at an altitude of 3300 m. The harshness of life in the high-altitude mountains is seen in the faces of local residents. It’s often difficult to estimate the age of people who have tanned faces, furrowed with deep wrinkles and exposed to winter frosts and sharp summer sun, dry climate and dust. Their eyes are dark but clear and bright and there is peace and calmness in their faces.

The visit here in the beautiful mountains, along with the effort that you have to put into each step, eventually takes everyone’s mind off things. You must be prepared for the fact that you have lost all of the securities you were used to, you must be able to adapt to what there is and accept whatever comes. Powerful experiences which you go through here will remain with you for the rest of your life.

Close your eyes just for a moment and imagine the snowy peaks of the mountains. Imagine that you are in the Himalayas. You feel the clear and crisp air, with every step you catch your breath, the sun beats down and when you come into the house, you can’t see anything – but you can smell the scent of India, of Ladakh…

Names of the families are listed according to the forenames of the adopted children because surnames aren’t used in Ladakh. Often, only a small number of names is in use and some of them are the same for both boys and girls. In the postal address, the name of the house where a family resides is the most important piece of information since this name is different from the names of the residents.

Boy, Jigmeth Dorjay, 12 years old (second grader)

He has three older brothers, one of whom is studying in a distant city Leh and the other two are living at home. Of all the families we’ve visited, his one is the poorest. His parents are unemployed. Everything the family owns are three cows and five goats. Jigmeth goes to school in the morning and in the afternoon helps his mother with the cattle, carries the water and then does his homework.

His father went to school and finished eight grades, his mother never went to school. Although they live in a large, two-story house, it contains almost nothing. Poverty is inscribed in the faces of these people and is present on every blank wall… We feel it as it touches us with its fingers… It’s hard to find the words. An invisible hand is choking me and I can’t breathe, but this time it isn’t from the lack of oxygen. It is the helplessness over the visible loss of hope which is reflected in the empty eyes of his parents. The boy was able to start attending a school only after being supported by a sponsor from the Czech Republic.

Families mostly live without fathers. We always find mothers with children at home, sometimes with a grandmother and grandfather who try to manage and maintain the household. The fathers earn money working in distant larger cities. They often work as taxi drivers and truck drivers; sometimes they serve in the army, which means they only see their families for just one month a year.

In the kitchen there is always a photograph of the father. If he is at home, our joy of the rare opportunity to meet the entire family is spoiled by the realization that the father has not found a job and the family has no income whatsoever. The family can’t buy anything, its members live in an empty house and scrape along. Investing in education, which could lead to a better future of the child, is their only hope. Private schools are able to provide quality education that is needed to find a good job but poor families don’t have enough money to afford it. Free public schools are of poor quality and their attendance barely leads to any progress; it’s as if the child never went there. There are usually more teachers in these schools than there are pupils, however, the teachers don’t go to work frequently, despite their regular salary. In this area, there are more of these schools than is needed; despite complaints from local residents over the quality of the education nothing has changed. It’s one of the reasons why many children whose parents don’t have the money for a private school don’t attend school at all. Children become more useful at home when helping with household chores and work on the field.

Boy, Padma Wangyal, 7 years old (first grader)

Padma is an only child, he’s very intelligent and apt. He is good at drawing and folding paper in a beautiful way. He is very energetic, and so he invites home a friend of his to play with. They are like brothers. He lives with his mother, father and grandmother.

The family lives in a strange one-storey house under a rock – in a home of the former Queen of Mulbeckh. In the 19th century the whole of Ladakh was an independent kingdom. Padma’s parents have not yet returned home, even though it’s already 7 p.m. We are welcomed only by an old lady (82), who is at home alone with the boy. However, she is already almost deaf and we really have to speak up in order for her to hear us. She is the only woman ever to be a head of a village (numberder), otherwise this function is held by men. Whatever is happening in the village, everyone comes for this person to ask for advice. Nowadays these functions are disappearing, the organization of the society has become different.

The evening comes and the mother still isn’t back home. She went to the mountains to get the animals that haven’t yet returned. The father came before the mother. Even though he doesn’t have a job he looks very proudly. He constantly observes everything and gives instructions. He behaves in a truly royal way, he welcomes us ceremoniously.

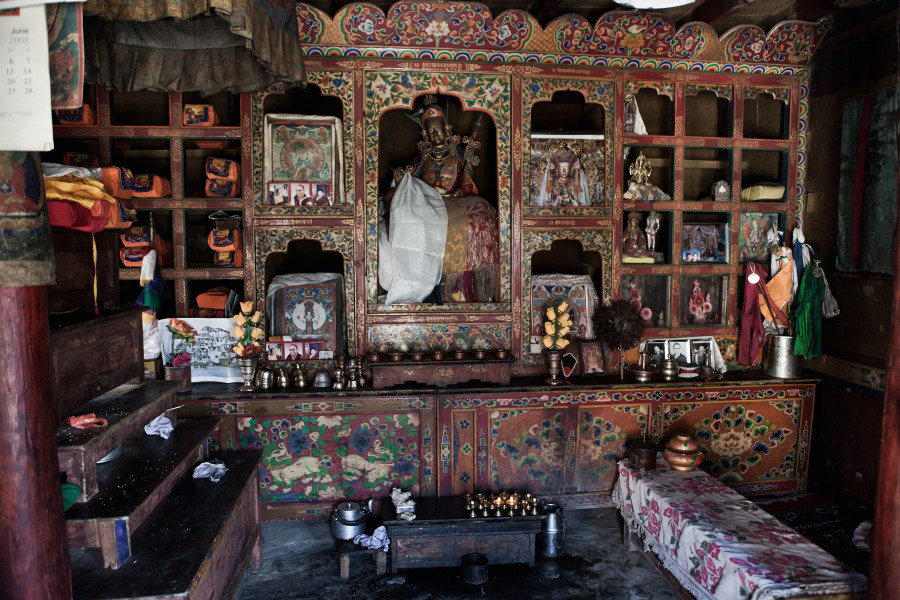

There is a praying room in every house. It often seems as if we were in a monastery. In old ornate painted showcases which the family has passed down for centuries, thousand-year-old sacred scrolls rest – sutras, statues of Buddha and other small Buddhist statues of prominent personalities; there are also photographs of the Dalai Lama. Compared to other rooms in the house, this one is relatively large and decorated. The grandmother shows us a photograph in which the grandfather meets Dalai Lama. The old lady puts on a traditional dress and presents herself in all its splendour. We get a simple but very tasty dinner and the mother finally appears – a truly graceful and beautiful woman.

We spend the night on the roof. Starry sky awaits us here, a cat passes by a few times and all we can see from the house before we fall asleep is the courtyard balcony – lit until the family also lies down to sleep. In the morning we get up and are invited into the kitchen for a breakfast. In this family, we are surprised by several things we hadn’t seen anywhere else: the boy is the first child whose mother gives him a handkerchief and who knows how to blow his nose! (however, first batch was experimentally thrown by hand out of the window). Most children in the school don’t know how to blow their nose and they have a thick noodle under their nose for the whole day (sometimes they manage to draw it inward before it leaves their nose again). Then his father helps him to get dressed. From his mother Padma gets a box of food for lunch and a spoon. He puts cream on his face and has a breakfast. After that he can go to school. The whole family anxiously see him off, everyone is involved in his departure to school. The pride of the historically unique position of the family can be seen in the way it takes care of the single child. It’s very modern for local conditions and everyone wishes for a better future for him.

Boy, Rigzen Chospel, 9 years old (fourth grader)

His father is a labourer, which means he goes from house to house and helps with whatever is needed. The boy lives in the house with his grandparents, mother, father and two siblings. His sisters go to a public school.

Even though the family is very poor, it seems to be united. Calmness and enormous humility can be seen in their faces. Great strength and peacefulness balances the absence of material provision.

Cohesiveness. That’s the first thing that comes to my mind when the family settles in front of us. This group, despite its unorganized, intuitive origin, looks very tight. Each member of the family has their place, their task; separateness and individualism wouldn’t work in the harsh conditions of the mountains. They all support each other and each one of them brings benefit to the whole family.

In India, loneliness, isolation, let alone expulsion from a group is considered to be the worst punishment. If someone finds themselves alone or separated from the rest, others rush to them to help, of only to help them by being present and sharing. If they have nothing to give, they at least give themselves and their time.

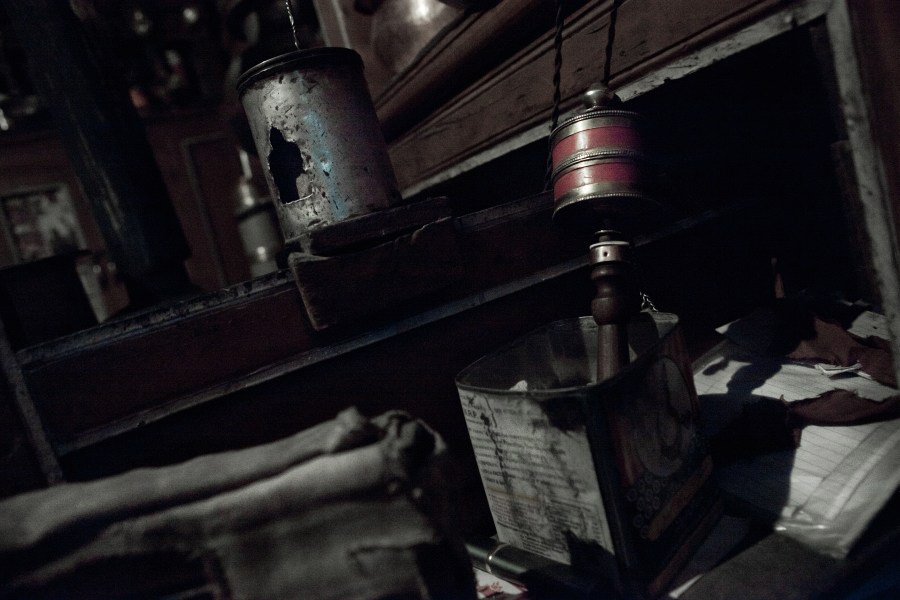

In most Ladakhi houses we are immediately blinded by absolute darkness as soon as we enter the front door. The house begins with a corridor that is not lighted, you can’t see anything, only a thin strip of light that comes from of the kitchen, where we are invited to. Even here it’s still too dark for us to see well. In the dark we see flashes of the polished containers which are stacked on shelves; the whole kitchen is filled with them. Some are used for storing food (flour, pasta, legumes, spices). The largest bowls are the oldest and they aren’t used anymore, they are inherited from generation to generation – most of the time the girl who gets married gets the dishes. There is a stove in the middle of the kitchen next to a supporting column and the chimney vent above the stove. There are peas and corn wrapped around the supporting column, depending on the season – it’s an offering to the gods to ensure a good harvest next year.

In the summer they cook on a small two-burner gas cooker, in the winter on the large stove, which is decorated with wrought-iron plate and heats the room, making it the only heated room in the house, even when the temperature outdoors reaches minus thirty to minus forty degrees. This makes it the place where the family gathers throughout the winter, where they manage to heat up the room to a temperature of about 10 degrees. Everyone also sleeps here, shortly after the family eats supper and when the food is warming up their stomachs. Before they used to gather together in one room with animals that produced heat. Winters are hard here with plenty of snow blocking the paths. The school is closed during the winter months – children have holidays from December to February.

Boy, Rigzen Nurbu, 14 year old (eight-grader) and boy, Stanzin Thubstop, 9 years old (fifth-grader)

Boy, Rigzen Nurbu, 14 year old (eight-grader)

His father works as a driver in Kargil and often isn’t home. When he comes back from school, Rigzen helps his mother carry the water and clean up. Then he does his homework and helps his younger brother with his. Six people live in the house, including Ritzen’s great-grandfather who is 97 years old.

and boy, Stanzin Thubstop, 9 years old (fifth-grader)

His mother is named Lhamo and she is a teacher in our school Spring Dales Public School. Now she is staying at home with a 1.5 months old baby.

The mother can stay at home for only three months, then she must return to work. Her mother and the rest of the family will then take care of the baby. Babies wear cloth diapers but older children – once they start moving around – only wear pants that are being constantly changed and washed when needed. Lhamo told us that she gave birth at home with the help of her mother who is a local midwife. Stanzin’s cousin from the village Fokar also lives with the family, because she goes to our school.

Most households have one or two cows for milk, as well as sheep and goats who provide some more milk but, more importantly, hair, from which women and men weave wool and woven fabric for the production of winter clothing. Another important raw material provided by animals are droppings, which are used as a fuel in the stove. There are no other sources for heating in this area because wood is not available in the desert landscape. People don’t keep hens, because hens would be hunted by wild dogs, and there’s also plenty of foxes in the area.

Wheat, barley, potatoes and peas are grown on the fields. However, vegetation period is very short here, roughly from May to August. The harvest is very important because it must provide adequate supplies for the whole year, especially the winter. There are only a few goods in the local shops, even in the summer time, in winter the roads are blocked by snow until late April and there is only a limited amount of non-perishable food in the shops. Therefore, when the harvest time comes, the whole family meets on the field, ploughing and sowing, including children who don’t go to school and fathers who take a leave from work at this time.

In the morning, the children wake up early – around six o’clock. They help to bring water or help around the kitchen as well as pray and prepare for school. About seven o’clock the local herdsman walks around, collects all goats and sheep and leads them into the hills for grazing. He returns with them only around six o’clock in the evening; every animal knows where it lives and finds the way into its cote. School begins at 10 a.m., but children have to set out on time. Depending on the distance, some children daily spend 1.5 hours on their way to school; they need the same amount of time to get back home.

Boy, Sonam Gurmath, 9 years old (third-grader)

His mother died and father remarried. A part of the family in which he lives is his foster aunt who takes care of him and his younger brother.

Their house is close to a large prayer wheel which is illuminated at night. People walk around the prayer wheels from left to right, spinning the cylinder. In the cylinder there are mantras written on paper scrolls containing the wishes of love for all living beings. By spinning the wheel all the prayers inside spin and fly to all the corners of the world.

We spent the night with the family. We slept on the roof, watching the sky full of stars, which seem so close here! A cool breeze caressed our faces. Before falling asleep I kept thinking about today’s evening, including how we played games with Sonam and how he enjoyed it. Sonam is the adoptive child of Jitka and she was touched by the meeting. The boy was incredibly shy at first, but when he was given a plush squirrel, he immediately hugged it. During the game, he talked to it and asked it to help him win. The plush toy immediately became his closest companion and he developed a personal relationship with it, one we hadn’t seen elsewhere. Is it because he lost his most beloved person, his mom?

In the morning, I got up very early, at 6 a.m. I went into the kitchen and we began to prepare a breakfast with the aunt. We sat on the ground; I cut a cauliflower and onions and she cut tomatoes in her hand. In total darkness the onion started to sizzle, we smelled the pleasant masala spice and she added cauliflower and tomatoes. Everything smelled nice, but I couldn’t see anything, I was groping around in the dark like a blind person and waited what would happen – do they actually cook here by heart? Suddenly a small light went on – a lamp. The aunt let the vegetables fry for a while, then poured the water in and let it stew. Once it started boiling, she took a large golden bowl, put it on the floor in the middle of the kitchen, sieved a lot of flour into it, added baking powder and then slowly poured in some water. She was kneading the thick dough by hand. She added cow dung and two branches into the stove and lit it. To my surprise a very pleasant smell filled the room! Above the fire, a small hotplate was slowly being heated. On a chopping board laying on the ground she rolled breads flat and put them on the hotplate; they quickly rose in volume and a number of bubbles appeared on their surface. After a while, Sonam’s stepmother came in and pounded salty butter tea in a large cylinder. Meanwhile the flatbread and steamed cauliflower were ready and we could eat our breakfast. It was delicious.

About an hour later we went out and opened the shed. Goats ran out and were impatiently waiting for the moment when they’d be able to go on their daily trip to the mountains for grazing. Suddenly a herd of goats and sheep appeared and a drover drove them ahead with loud hissing. Goats from our house gleefully joined the stream and so did the goats from the neighbours and other nearby houses. We all quickly ran behind the flock but in the winding streets we soon lost the sight of them. It didn’t take long and we saw them in the distance on the hills, still heading upwards.

Only two cows stayed at home and, from a water bowel, they were fed waste from the cauliflower that I had been chopping in the morning. All ingredients were carefully utilized and nothing was wasted.

Girl, Tsewang Dolma, 15 years old (ninth-grader)

For most of the time, Tsewang lives only with her mother because her father and brother both work as taxi drivers in a faraway city. Their house is one of the few houses hidden among trees and it has its own fenced in garden – a park where young Tsewang has been growing up and playing. The family owns two cows. Tsewang’s favourite food is chow mein noodles.

Houses usually have only one floor but there is also use for their flat roof. Between the floors there are stairs – ladders. Sometimes they are very wobbly, made of thin, crooked rungs and when I go back down, I feel dizzy becuse there is nothing to hold onto and I am headed into dark emptiness. The roof is not used just as a place where the family sleeps in the summer but it is also used to dry hay for animals for the winter along with cow dung, which is used for heating in a stove. The dung can also be dried on small walls and in other places in the sun; when dry, it is put under a roof, in a corridor or in a courtyard balcony so that it is accessible in the winter. If there is a bundle of long poplar tree branches which is being dried, it means the branches are prepared to be used for the roof.

During the visits we do our best to follow the local customs, such as refusing tea and refreshments at first; as the number of visits grows, we take advantege of this custom because the sweet milky lake in my stomach is starting to make me feel unwell. In some households we also receive salty butter tea, which is churned in a long cylinder. Some foreigners struggle with its taste but I like it a lot. Another custom is to avoid stepping over small tables, food, religious objects and people who are lying down, since feet are seen as unclean. Moreover, feet should never face other people or a kitchen stove. Because the space is small, this becomes rather challenging – we need to leave our legs hidden somewhere behind our body but we are not able to stay in such position for long.

Boy, Stanzin Nima, 9 years old (fourth-grader) and boy, Tsewang Tonrab, 6 years old (pre-schooler)

Boy, Stanzin Nima, 9 years old (fourth-grader)

Stanzin’s father works as a driver in Jamm. Stanzin likes chemistry, physics and biology. He lives with his grandmother, her daughter – the mother of the children – two brothers and a great-grandfather, who is 87 years old. Stanzin likes taking care of his younger brother and enjoys teaching him how to draw. We keep asking about the great-grandfather’s age for a while because it is not quite clear whether he is a grandfather or a great-grandfather and if he happens to be 84 or, for example, 92 instead. The family is throwing around all sorts of numbers. Finally, they agree on 87 and we decide to believe it, even though I feel like the family has just came up with the number now. We are even more surprised when we visit families where the age of children whose names we have written down in a list provided by the school is unclear. In the end, we do not know if the pupil is 10 or 12 years old because neither the pupil themself nor the family, including the mother, knows this. No one here keeps a record of who was born, when and how old they are – it is not important. In fact, the families laugh at our questions, not understanding why we put so much energy into finding the exact date.

and boy, Tsewang Tonrab, 6 years old (pre-schooler)

Tsewang’s father serves in the army and comes home only to help with the harvest. The family is very poor. At the moment they have a small kid with soft fur and the children enjoy playing with it.

In the corridor there is a head of a bird of pray and claws hanging together. They are believed to protect the inhabitants of the house from everything bad. The guest room is covered with beautiful carpets, around the walls there are mattrasses or blankets to sleep on and in front of them there are small tables. There are no other things or furniture in the room. It is always clean and ready for guests. However, when we spend the night with a family, we are invited to sleep on the roof during the hot summer, since there are also unwelcomed guests in the guest room – bedbugs hiding underneath the carpets.

In one of the families we have visited they tell us about a grandfather who was an oracle. This is an ability which runs through the family, manifesting itself every other generation. An oracle carries a sword, can predict the future and guides those who come to them through their life. They can be faster than a car, dance in a fire and they watch everyone who does not wear traditional clothes. It is not a good idea to take pictures of them because they might become angry and take your camera away. In any case, they will catch up with you.

Boy, Stanzin Stanskyang, 6 years old (first-grader)

The family has five children – three brothers and two sisters. The oldest children are independent now, not living home anymore – one of the sisters studies in Leh, one of the brothers is a monk. The father works as a labourer in a village near Kargil and travels home from time to time. Great-grandparents, the father, mother and two children currently live in the house, which has a spaceous kitchen. The house is very far from the school and Stanzin is the youngest one in the village. Other children come for him and go with him so he does not have to walk alone.

Sources of water are usually far away from homes and children help to carry it home in cans. There is a river running through the valley. Its water comes from melting snow and glaciers from high mountains; there is no rain in the area. The locals cleverly distribute the water through the village and their fields by using canals. By doing this, they create beautiful green oasis in the rocky landscape. The canal leading through the village, with small channels diverting the water into the fields, is pluged at every opening by a piece of cloth and a stone. The families have agreed which days of the week which family can open their barrier and let the water into their field. People conserve water in the homes. There is a small bucket we can use to wash ourselves – clean our face and brush our teeth, either above a bowl or above the ground, where the water gets absorbed. We try to clean ourselves with as little water as possible. When we see children in the morning, carrying water in their thin from afar for the whole family, we do not dare to waste it.

Time passes by differently in high mountains. It is difficult to breathe here, the body fights with lack of oxygen, you have to move more slowly, it is easy to catch a viral infection, you struggle with indigestion and don’t feel hunger, first days you fight headaches, sore throat, pain in lungs and swollen mucosa, you cannot sleep, your heart beats very fast… All this forces you to slow down. The first week you clense your body and purify your soul from everything you brought from home. Only the important things remain in your mind and you rise above issues which seemed insolvable at home.

As we come closer to the last family for the day, my legs are becoming heavier and heavier and I have to muster all my strength to climb even a small hill; I am trying to catch my breath. I am the last, the rest of the group is ever further so I am trying to walk faster and stumble along the path, hoping not to lose sight of the group. Finally we are in the kitchen. I sit down and immediatelly fall to the ground; closing my eyes, I fall asleep in no time. My throat is sore, I am shivering, fatigued. I will not take any pictures here, I have no strength left…